MASONIC EDUCATION

Early Establishment of

Masonic Regulations

EXAMINING THE HISTORY

IN ANCIENT MASONIC TEXTS

On June 24, 1717, St. John the Baptist Day, four London Masonic Lodges for a unified organization under the name, Grand Lodge of England, This Grand Lodge proclaimed itself to be speculative, meaning deeply philosophical. In the early 1700s, most speculative masons were churchmen or members of the nobility. After Freemasonry emerged into public view after 1717, a treasure trove of ancient Masonic manuscripts was discovered and made public. These parchment manuscripts became known as the Old Charges, to distinguish them from newer documents. The ancient documents described how a Mason would be “charged,” or obligated to follow good rules to work and live by. Each rule was couched in the work of operative Masons but was considered good advice for anyone.

The Scottish Pastor, Reverend James Anderson, was one of the individuals involved with the establishment of Grand Lodge, and accordingly had access to all of the above Old Charges. From them, he drew much material used in his influential book, Constitutions of the Free-Masons, published 1723.

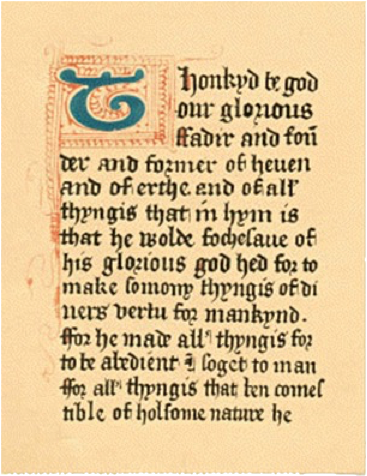

Returning to those ancient documents which are housed in the British Museum, we find that the two most significant ones are (1.) the Regius Poem or Royal Manuscript, also called the Halliwell Manuscript, and (2.) the Cooke Manuscript.

The Regius Poem

The Regius Poem was apparently written by an English Cleric about 1390. the first sentence was written in Latin, the rest in Old English. This indicates that the author was a highly educated person who also had a high degree of literacy. It is a complete poem of 794 verses and claims to be derived from much earlier texts, in more modern times, it was published by Jamies Halliwell in 1840.

Verses 143-46 seem to show that Freemasonry was open to accepting members who were not “artisans of that craft.”

By olde tyme wryten y fynde

That the prenes schudle be of gentyl kynde

And so symtyme grete lordys blod

Toke thys gemetry, that ys ful good.

(By old time written I find

That the ‘prentice should be of gentle kind;

And so sometime, great lords’ blood

Took this geometry that is full good.)

Regis was the only Old Charge written as a poem. Due to its age and unique content, Regius provides a remarkable window into the years following the disappearance of the Knights Templar.

The Cooke Manuscript

The Cooke Manuscript appears to have been written about 1410 and appears to also have been translated from a much earlier text, which was “translated” from Middle English into Modern English by Matthew Cooke. The first two articles illustrate how Freemasons were “charged” to lead a good life.

The first article is this. That every master of this art should be wise, and true to the lord who employs him, expending his goods carefully as he would his own were expended; and not give more pay to any mason than he knows him to have earned, according to the dearth [or scarcity and therefor price] of corn and victuals in the country and this without favoritism, for every man is to be rewarded according to his work.

The second article is this. That every mast of the art shall be warned beforehand to come to his congregation in order that he may duly come, unless he may [be] excused for some cause or other. But if he be found [i.e., accused of being] rebellious at such congregation, or at fault in any way to his employer’s harm of reproach of this art, he shall bot be excused unless he be in peril of death, And though he be in peril of death, yet must he give notice of his illness to the master who is the president of the gathering.

Origins of Early Masonic Teachings

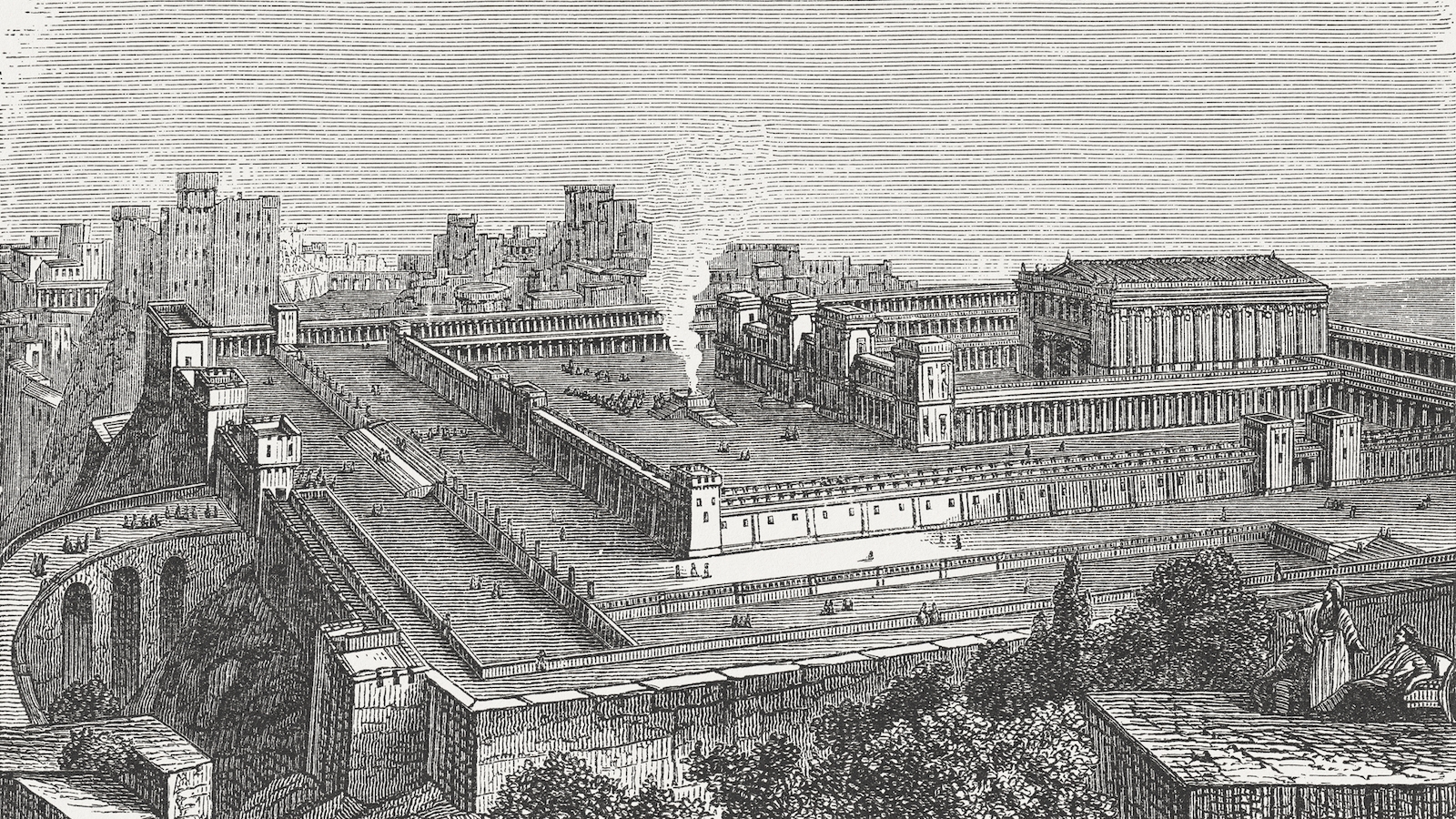

Masonic teachings, both architectural and philosophical, evolved from the teachings of the Roman College (Collegium) of Artificers (Builders), which was founded in 714 B.C. by King Numa Pompilius, and from the teachings of the Comacine Masons, an architectural school founded in northern Italy after the collapse of Rome as a power in the 400s A.D. And of course, pre-dating the Artificers and the Comacine Masons was the construction organization that built King Solomon’s Temple about 1,000 B.C. Let us examine each of these influences in turn.

The building of King Solomon’s Temple is the founding legend of Freemasonry. The Craftsmen directed by Master Mason Hiram Abiff labored to create the perfectly proportioned mystic edifice that would house and celebrate the presence of the Lord. Tradition tells us that there were employed in its construction three Grand Masters, 3,300 Masters or Overseers of the Work, 80,000 Fellowcrafts or Hewers in the mountains and quarries, and 70,000 Entered Apprentices or bearers of burdens. The Temple was completed in 960 B.C.

The Roman College of Artificers had certain operating features, such as being a mini-government operating under its own statutes, exercising the power of making contracts as a corporation would, with immunity from taxation. Its meetings were held in privacy, in similarity to the exoteric schools of the philosophers. It places its members into one of three classes, corresponding to the three levels of membership in modern Masonry. It also admitted into its ranks men who were not strictly speaking operative Masons by employment. This closely parallels the much later situation in late Medieval Masonry, when operative lodges gradually admitted gentlemen of learning, they being considered the first “speculative” Masons. Finally, they used a symbolic “language” allegorically drove from Masonic implements, and they conferred on their initiates secret modes of fraternal recognition.

As the Roman Empire declined, the Comacini Masons continued on a similar course, to them, we owe the development of the Romanesque style of architecture in about 600 A.D. This style has roots in Germany, France, and England. In similarity to our modern Masonic system, the Comacini had Masters, Wardens, signs, tokens, grips, passwords, and oaths of secrecy and fidelity.

Next we encounter the legendary establishment in England of rules for proper Masonic behavior. About 926 A.D., according to the Regius Poem from the late 1300s, Athelstan, an early Danish King of England, together with his brother Edwin, gathered Masons and their charters and rules of behavior from many European jurisdictions; these were unified into a code of conduct for the wide-area around Your, England Athelstan also granted the Masons a royal charger officially recognizing the Masonic Guild. This Guild carried out many functions of molder labor unions — it set uniformed waged, it trained apprentice stonemason, and it encouraged Masons to look out for each other. It also protected the trade secrets that made Masons the most highly-paid workers in Europe. Finally, Masonic guides developed and employed seated signs of fraternal recognition — signs that a Mason traveling to a distant building site might use to prove that he had been properly trained during an extensive apprenticeship.

My point here is that all of the behavioral influences occurred well before the middle Medieval Period when operative masons were employed by the Cistercian Monks to erect Europe’s magnificent cathedrals. Thus, it is not surprising that allegorical Masonic symbols do not include Medieval symbols, such as the Flying Buttresses of great cathedrals, but instead include simple tools (compasses, spare, plumb), and focus on ancient edifices, such as the Great Pyramid, with the All-Seeing Eye of God superimposed on it, and King Solomon’s Temple, with its ending staircase and Middle Chamber.

The Influence of the Knights Templar

Before we examine the entirely separate Templars, there was a spiritual outgrowth among Masons in France in the 1100s, encouraged by St. Bernard of Clairvaux. These Masons were building great European Cathedrals, such as the Chartres, in northern France. However, the design work of two particular Master Masons at Chartres especially reflects a metaphysical, spiritual, and (in the lingual of Freemasonry) “speculative” character. This is proof that even before the late 1300s ear of the Regius Poem, a philosophical side to Masonry was developing.

In 1118, an entirely separate group was created, called the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon; we call these groups the Knights-Templar, or Templars. They were established within a secret cabala, the Troyes Fraternity, headed by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Pope Honorius II, the Count of Champagne, and influential others. Their original purpose was to venture to the Holy Land, secure material and informational treasure from King Solomon’s Temple, and return with it to Europe, especially France, They also built circular-shaped churches across Europe — particularly the British Isles. They come into this story because the Templars were declared heretical and were dissolved between 1307 and 1312 — not through their own fault — and remnants of Templar Commanders throughout Europe ran to Masonic Guilds for protection and survival. Although this speculation, I’m sure that the grateful Templars share their cast wealth with the Masons, in exchange. Of course, we now have the situation that fraternally recognized Templarism is entirely within Masonry.

These Templars were given the use of certain lands in eastern Scotland as a dowry in about 1140, when their first Grand Master, Hugh de Payens, married Katherine St. Clair, daughter of an influential Scottish family. It was on this land that Rosslyn Chapel was constructed between 1442 and 1484. The Chapel was likely constructed to secretly house Templar treasure, which had been stored in the Templar-associated Chartres Cathedral in northeastern France until it could be transported to Oak Island in Nova Scotia, site of the famous “Money Pit.” This area is still being actively and productively excavated. The Templars were not really construction experts, and nearby Rosslyn Castle was an instance of cooperation between Templars and operative Masons.

As I have outlined, the establishment of Masonic regulations, both in the architectural realm and especially in the area of the rectitude of conduct in dealing with each other, and with others, including their Cistercian “construction bosses,” was a long and gradual process, influenced as it was by the was of the Roman Artificers and Comacini Masons, likely by the legendary York Assembly in the 900s A.D. and the “Points and Parts” contained in the Regius Manuscript. These regulations, fostering gentlemanly behavior among operative “Brickies,” suggest to me that the move from Operative to Speculative Masonry was not the sudden shift often mentioned as occurring about 1600 — although this was when non-operative Masons were first admitted — but in terms of the behavior of Operative Masons, was a gradual process over the centuries.

Bro. Jim Simpson, Schenectady Lodge #1174, Schenectady, New YorkSigman Bodies Ancient Accept Scottish Rite, Scotia, New York St. George’s Chapter #157, Schenectady, New York St. George’s Council #74, Schenectady, New York St. George’s Commandry #37, Schenectady, New YorkCharles H. Copestake #69 AMD, Schenectady, New York