MASONIC ART

Masonic Aprons

A Marriage of Art and Freemasonry

One of the most beautiful and inspiring aspects of the Craft is the Masonic apron. The inspiration does not exclusively lie in the meanings of symbols. Masonic aprons, an essential and most meaningful component of Freemasonry, have not yet found their deserved place in the world of art and collectible artifacts. Generally speaking, Masonic aprons are appreciated mainly by members for their value in ritual or use in Lodge functions. However, such an essential aspect of the Craft is not yet receiving the appreciation it deserves. Masonic museums and libraries have beautiful collections of aprons.

From its inception, art has been integrated into every visual within Freemasonry. However, after the Second World War, as members began to dwindle, so did Masonry’s integration of art. What follows here is a brief history of the Masonic apron, the techniques employed, and the type of artists who created these beautiful and meaningful artifacts of Freemasonry. Throughout the years, the techniques used in creating Masonic aprons have encompassed painting, embroidery, and engraving. The types of aprons have also ranged from folk art, often created by self-taught painters, to those aprons made by accomplished artists.

Pictured: PHOTO OF ROYAL ARCH MASON 1850’s-1860’s

Judging by the photo, his apron and baldric are both embroidered.

Handpainted

Hand painting Masonic symbols on aprons was the initial technique used for decorating aprons during the 18th century. Incidentally, the painted aprons are my favorites. Artists used water-based paints in rendering their designs. On occasion, gold leaf would be added. The surface material would be either silk or leather. Silk aprons often consisted of three individual layers. Underneath, one might find burlap to ensure sturdiness. Finally, the backside would get a soft lining material to maintain a consistent presence on the front and back. Sometimes other materials, such as linen or cotton, were used to paint on, but they would be the exception. There were also two-sided aprons that featured imagery on both sides.

A classic example of Masonic Folk Art. Probably dating back to the 1840s-50s, this historic Masonic Apron was painted by a woman. We know this because her business card was attached to the back of the apron. She was most probably self-taught but based on her business card, she was taking on commissions. The lady certainly had some understanding of the subject matter. There is some speculation that the artist might have been an ancestor of President Harry Truman, a prominent mason himself. The flap here is purely decorative, as in the tradition of many of the oldest aprons. The apron is silk. The symbols were first outlined in pencil and then colored in with watercolor.

AN EARLY APRON PAINTED BY A WOMAN

AN EXPRESSIVE PAINTED APRON 1790’s-1800’s

Dating to circa the 1790s-1800s, this expressive historic apron features both depth of color and great style. The colors display an intensity that is quite impressive The images are beautifully rendered with fine use of light and shadow. The subtle sophistication of technique and design sets this apron apart from the previous folk art examples, all of which point to this being the work of an experienced artist. Based on the strength of the colors, one might even mistake them for oil paint, although the artist may have used tempera which is a water-based medium. The decorative fringes and trim are metallic silver. The apron is triple-layered. The front is silk, reinforced underneath by burlap material with a lining on the backside. The apron might be of European origin.

Methods for painting the aprons differed. Many artists first penciled in an outline of the composition, which would be colored in with paint. Some began by laying down the imagery by use of stenciled designs. Yet, other artists felt secure enough to render their imagery completely free-handed. Apron designs were not yet standardized in the early days, meaning that no two aprons were identical (unless a copy was made).

Throughout the years, the aprons’ flaps changed and evolved, as did the shapes of the aprons themselves. The flaps on the earliest aprons were mainly symbolic rather than functional. Trim was used to create the illusion of a flap. It could not be lifted. In due time, flaps were made to be useful. Underneath could be inscriptions, initiation histories, or the craftsmen’s logo, or left untouched. As to the shape of the aprons, initially, many aprons were rounded, and some were rectangular. The rounded aprons eventually became less popular, and the rectangular shape became prevalent. Some triangular aprons are still in use today.

SCOTTISH RITE APRON BY FEMALE REGALIA MAKER

Over the course of the 19th century, painted aprons began to gradually fizzle out. Subsequently, the engraved ones came into prominence. However, the painted aprons never disappeared from use entirely. Even during the early 20th century, there were some lodges that required aprons with painted designs. And here we come to Miss Rose Lipp of Boston, the owner of a company that manufactured and sold all manner of Masonic and other fraternal society regalia and swords. Her employees also included artists who painted aprons on special commission. This circa early 1900s triangular Scottish Rite 22nd Degree apron is a Rose Lipp creation. It appears to be painted on leather. In spite of the relative simplicity of execution, we would not consider this to be folk art.

This is a very beautiful early piece. While deceptively “folksy”, it was most certainly painted by a trained artist with the aim of maintaining a spirit of simplicity in execution. The use of color is striking. There is both subtlety and strength here. Take note of the dramatic shadow effect behind the beams of light surrounding the All-Seeing Eye. Then there is a fine delicacy in the blending of color, most noticeable within the blues and greens. This apron includes the use of gold leaf. The material is very delicate silk. The flap is purely symbolic and cannot be lifted. The borders consist of three elements; two silk ribbons and outer fringes.

PAINTED APRON 1850’s-60’s

ELABORATE SYMBOLIC COMPOSITION, PAINTED APRON

Here we see the extent of freedom artists often enjoyed when creating aprons. This 19th-century apron features an elaborate composition comprised of a great many profound icons. The color scheme is vibrant and lyrical. The symbolic design goes right up to the borders. The piece is most inspiring. It is important to appreciate how the prior absence of rigid standardization of design allowed artists to better convey the beauty and spirit of the Craft.

The Odd Fellows, more than any other fraternal order or so-called “secret society” was the closest in spirit and culture to Freemasonry. One could call it a child of the Craft. Like Masonry, the Odd Fellows originated in Europe. In their heyday, it is believed that almost three-quarters of Odd Fellows membership consisted of Masons. Dual membership in the two organizations was very common. This magnificent circa 1850’s Odd Fellows apron was painted on leather. The influence of Freemasonry is obvious. The use of symbolic aprons by countless numbers of subsequent groups would never have happened had it not been for Freemasonry.

ODD FELLOWS PAINTED 1850’s APRON

PAINTED APRON MADE BY GRAND LECTURER OF NEW YORK

This circa 1840s-1850s painted Royal Arch apron was made by Bro. BW. H. Drew, Grand Lecturer of the Grand Lodge of Free & Accepted Masons of the State of New York. At the time, Bro. Drew operated a very small Masonic and Odd Fellows Regalia company that specialized in both customized and manufactured regalia. Whether Bro. Drew himself painted this apron or had an artist in his employ make it for him, we may never know. But it is clear that an accomplished artist was the creator. The flap in this case is functional. Underneath it, one finds Bro. BW. H. Drew’s logo. Exactly how many or few or any other of his creations have survived these many years is anybody’s guess. This is the only one I have thus far seen.

Engraved

These are often just as remarkable in their beauty as are the painted examples. Rarely is there anything overtly “primitive” looking about them. Engraved aprons were known for their classical and sophisticated appearances. For the most part, the artist who designed the original composition was not the person who would eventually print the engraved imagery on the apron. Processes varied. The most direct technique was where the artist himself would engrave the metal plate. Even in that case, the artist probably did not print the image. The task of printing would be relegated to someone else. Many engravers were also printers, but not all. In some cases, the artist would draw the design on paper to be transferred by a professional engraver onto a metal plate for printing. Then a printer did the printing. The great 19th-century French illustrator Gustave Doré, for example, never engraved his images. He created them as a drawing to be produced by an engraver in the printing process.

DYNAMIC ENGRAVED 19th CENTURY APRON ON SILK

In the photo above, the artwork on this early 19th-century apron concerns itself more with overall form than with particular details. The result is a powerful composition comprised of iconography rendered on glowing white silk with black ink. The effect is quite dramatic. Unlike painted aprons, it is more common to find a discreetly placed artist’s signature on some engraved aprons. A printer’s logo often appears on the backside, but on occasion also under a flap. All parties, artists, engravers, and printers were masters of their Craft.

ENGRAVED SQUARE AND COMPASS APRON by POLLARD

Early engraved aprons could be printed on silk or cloth surfaces and only occasionally on leather. This masterfully engraved circa 1830’s apron was made by the great Boston engraver and maker of regalia Bro. Abner W. Pollard. Stylistically, this piece focuses on powerful renderings of the Square and Compass and All-Seeing Eye. Abner W. Pollard was both a Freemason and an Odd Fellow. He also served as a City Councilman. As a Mason, Bro. Pollard belonged to the Scottish and York Rites. He held office in the Royal Arch and the Knight Templars. Bro. Pollard’s son eventually inherited the business.

Embroidered

Never underestimate the significance of embroidered aprons. Unlike the engraved versions and more like the painted ones, embroidered aprons can be highly ornate and intricately detailed. Still, they can also show the charmingly quaint qualities of folk art. European embroidered aprons are particularly masterful. British Freemasonry, for example, is well known for exquisitely ornate embroidered Scottish Rite aprons. Although these three techniques: painting, engraving, and embroidery, were used independently, on rare occasions, all three methods were used together. At times, jewels were added.

EMBROIDERED FRENCH 1780’s-90’s APRON

Interpretations of Masonic symbolism have varied according to country or jurisdiction. There are also symbols that are not used universally in Masonry. And then there are many symbols that once appeared on older aprons that have long since been discontinued. The core of this unique circa 1780’s-1790’s apron from France was created through the imaginative use of embroidery. The iconography is fabulous. Do take note of the picturesque imagery, a bridge overlooking a river with three skulls, a uniformed and faceless golden gladiator, eagle, and the triangle with Deity symbolism. I myself have seen only a few aprons bearing this particular design. All were in European collections and probably very rare.

This 19th-century apron has integrated several techniques. First came the engraved design. Subtle color paint and applied gold leaf were then added to give the apron a stronger presence.

MIXED TECHNIQUES APRON

As for the artists themselves, some were Masons while others were not. Most were probably men, but more than a few were women. We can presume that those women who created these aprons were either married to Masons or were somehow related. Considering the solid esoteric symbolism portrayed, those gifted women must have had some knowledge of what they were painting. Perhaps their husbands played a little loose with some “secrets” when it came down to getting an apron made.

There were essentially two types of artists who created Masonic aprons: the self-taught and so-called “folk painter” and the highly skilled, or “professional” artist. The folk artist’s work shows excellent charm and spirit and can even be haunting and surreal. The “professional” artist, who, whether academically trained or self-taught, created work that displayed mastery of technique and a sophisticated style. Unfortunately, whether folk artist or professional, most of their names have been lost to history as relatively few Masonic aprons had signatures.

Masonic aprons, being professionally painted or created by amateur artists, have always been a part of art history from the late 1700’s up through the centuries. Ever since the 1960s, American and European folk art, while for the most part previously neglected, rose to prominence in the mainstream art world as well as in the antique marketplace. For many years now, museums and galleries the world over have mounted extensive exhibitions of artwork labeled as “primitive,” “folk art,” “naïve,” and now also as “outsider art.” The American politician and art collector Nelson Rockefeller was an early collector and promoter of American folk art. Today, there are many prized collections of folk art around the world. No doubt much of Masonic apron art and other of Masonry’s crafts qualify as being folk art. But these fabulous pieces are underrepresented in exhibitions of art, most often completely overlooked or purposely ignored. This is very curious because so many of the world’s prominent historical figures have been Freemasons. Could this under-representation be a residue of the ancient legacy of anti-Masonry? Whatever the case may be, it is time for these beautiful, finely crafted historical works of art to be lauded, displayed, studied, and appreciated for their genuine value as fine art.

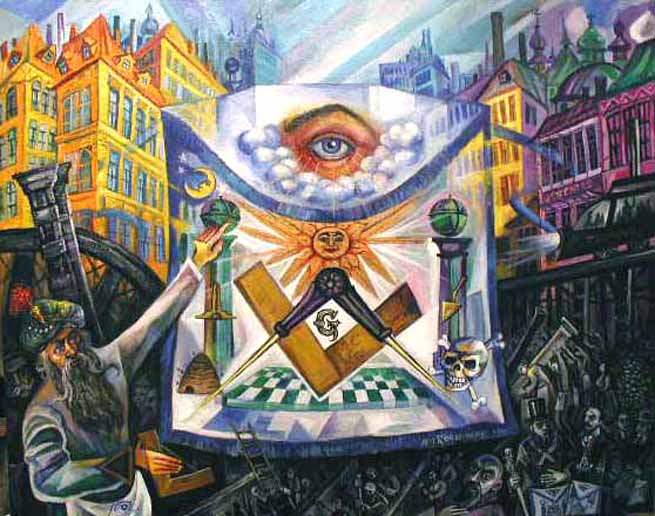

HIRAM’S APRON by ARI ROUSSIMOFF

Being a painter myself, I believe it was the apron’s artistry, which led me down the path to eventually join the Craft. Years later, and very much inspired by the historic aprons, I began to create my aprons. I paint them from my perspective and never copy or imitate the classic ones.

With a more public focus on Masonic aprons and other Masonic artifacts’ beauty and spirit, perhaps they could reach and inspire interested gentlemen, as I once was, to seek their interest in the art, culture, and philosophies of Freemasonry. This path will ultimately lead to a lifelong journey of pursuing the virtues and meaning of our beloved Craft’s historic principles.

www.Roussimoff.com

Consolidated Lodge #31 F. & A.M.

Manhattan, New York