The Pride of the Fraternity

The Pride of the Fraternity

“A distressed, worthy brother and his widow must be comforted and guarded so long as the obligation, which makes us Masons, is cherished and remembered.”

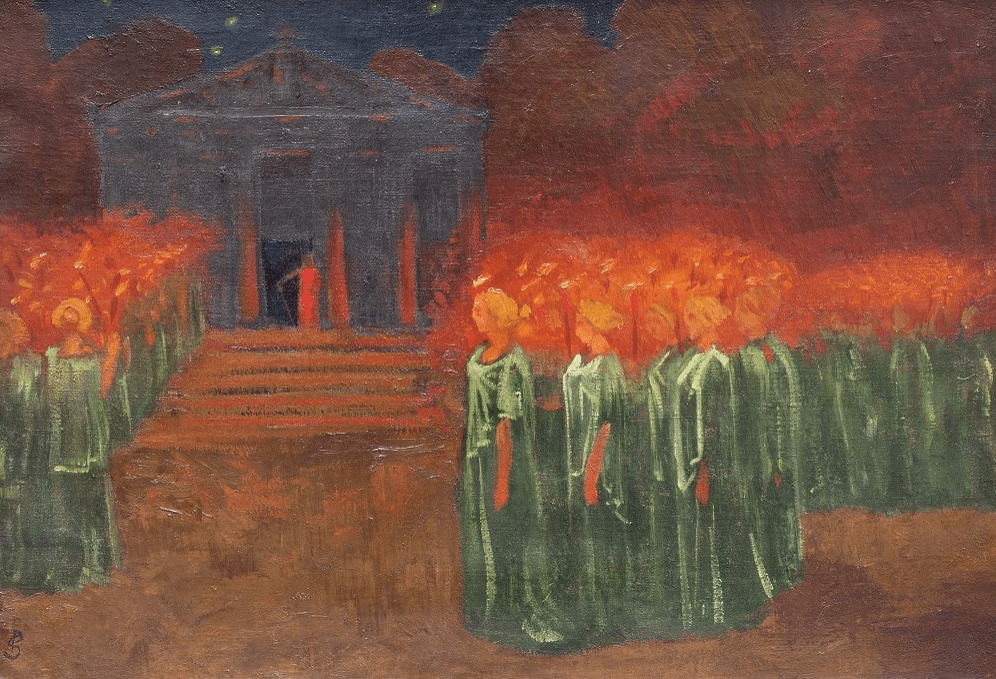

Photo: Masonic Home of Utica

M.W. James Ten Eyck, Grand Master, bellowed those eloquent words on June 7, 1892, during the Grand Lodge of New York’s Annual Communication, and went on to regard the new Masonic Home of Utica as “the Pride of the Fraternity.”

Nearly 181 years ago, the Grand Lodge of the State of New York began the illustrious and monumental project of erecting a home for ailing Masons, their widows, and orphans. In 1842, a building fund was started, with a $1 subscription, and paid at the time by Grand Tiler Greenfield Pote, after the project had been commented on by Grand Secretary James Herring. This dream finally became a reality a year later, on June 8, 1843, when 100 Masons signed a petition for the purpose of founding the asylum.

Committees were formed and, by 1851, a recommendation was made to purchase property in Utica because it was located in the “center of the state,” and would be most central for New York Masons. The site was to be placed on “Utica driving park,” which had been used for State Fairs, and sprawled across 230 acres.

Several audacious fundraisers were launched, specifically in 1887, led by the Ladies Masonic Fair Association. The event held in New York City netted $76,000 and helped contribute to the estimated $175,000 needed to begin building the site. Grand Lodge added a $3 per capita assessment in 1889 to help meet the financial needs for the Masonic Home.

On May 21, 1891, the cornerstone, which was hewn of Quincy granite and weighed 1,750 pounds, was laid by M.W. John W. Vrooman, Grand Master, who wielded a magnificent silver trowel during the compelling ceremonies, as brass bands afterward serenaded throngs of spectators, including 6,734 Masons.

Renaissance architecture was chosen for the design, and the material used consisted of quarry-faced stone, with trimmings of brownstone, and Philadelphia front brick for the upper stories. The woodwork was of oak, ash, and white pine. The main center building was for the administrative offices, while the wings were devoted to rooms for patients. The basement contained two large swimming pools, playrooms for children, and dormitories for the workers. The first story had offices, and staterooms, and the second story provided additional dormitories for resident staff, and children. The third floor offered lavish offices and common rooms, and the fourth story was used as an infirmary, subdivided into five rooms for men, women, boys, girls, and nurses.

The City of Utica graciously contributed $30,000 toward the project, and the cost of the home upon completion was roughly $182,000.

On October 5, 1892, the Masonic Home was dedicated by M.W. Ten Eyck and the site officially was opened. “The doors of the home [have] swung wide with true Masonic hospitality to the Brethren of the Craft and their widows, who have needed a friendly and kindly environment in which to wait for life’s sunset, and to the orphans, who in youth needed the protection of affection and incentive for high living and true citizenship,” exclaimed Ten Eyck. “[May] God grant never to close as long as the human heart beats in sympathy with our Brothers’ woes.” Upwards of 8,524 Masons, donning the white lambskin, proudly marched six miles for a grand parade from Bagg’s Hotel to the new Masonic Home. Dignitaries were on horseback, others in carriages, and George Washington’s Bible illuminated the large procession.

On October 5, 1892, the Masonic Home was dedicated by M.W. Ten Eyck and the site officially was opened. “The doors of the home [have] swung wide with true Masonic hospitality to the Brethren of the Craft and their widows, who have needed a friendly and kindly environment in which to wait for life’s sunset, and to the orphans, who in youth needed the protection of affection and incentive for high living and true citizenship,” exclaimed Ten Eyck. “[May] God grant never to close as long as the human heart beats in sympathy with our Brothers’ woes.” Upwards of 8,524 Masons, donning the white lambskin, proudly marched six miles for a grand parade from Bagg’s Hotel to the new Masonic Home. Dignitaries were on horseback, others in carriages, and George Washington’s Bible illuminated the large procession.

The following year, M.W. Jesse B. Anthony, Past Grand Master, was installed as Superintendent, and the first Mason to be received as a resident was Brother James Borden of Greenwich Lodge 467.

During its early years, the Masonic Home offered large rooms that accommodated from two to six people each. The area also featured impressive reading rooms, a billiard hall, a smoking and lounging room, a sun parlor, and an on-site hospital. The site also included a school for kindergarten through fifth grade, and offered a playground and other amenities for children.

From 1892 to 1911, the site cared for 191 children, 892 adults, and operated with a staff of seventy. Rising hour was 6:30 a.m., and lights out was 10 p.m.

Today, the Masonic Home is named the Masonic Care Community, and is a first-class facility that serves 500 people on a majestic 400-acre campus. The mission continues to “support, nurture, and educate” those in need. The center does this by “providing exceptional care and services with compassion and pride guided by the Masonic Principles of brotherly love, relief, truth, and integrity.”

Interesting Facts:

- The site at one time bolstered an impressive farm: 104 cows, seventy-five pigs, sixty sheep, and plenty of chickens.

- At least twenty-three boys who grew up at the Masonic Home valiantly served their country during World War I. Three were wounded in battle.

- During the early 1920s, the cost of maintenance averaged $200,000 annually.

- The Masonic Home once used more than 3,000 tons of coal a year.

- Fifty barrels of flour were once used per month.

- Upwards of 25,000 visitors came every year.

Sources:

Lang, O., History of Freemasonry in the State of New York, Grand Lodge of New York, 1922.

Greene, N., History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614-1925, New York State Masonic Home at Utica, 1925.

Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York, 1892.

The Illustrated American, June 13, 1891.

The Masonic Home, The Trustees of the Masonic Home and Asylum Fund, 1911.

By W. Bro. Kyle A. Williams

Bro. Williams, a collector of New York Masonic history, is Worshipful Master of Wallkill Lodge 627 in Walden, New York, where he also is lodge Historian.