In Ancient Egypt, sacred spaces for initiation rites were integral to the cultural and spiritual life of the society. These spaces, often majestic temples, were far more than architectural achievements; they were central to Egyptian spiritual practices, providing a venue for significant transformational processes. The Egyptians believed that for an initiation rite to be fully effective, it needed to be held in a space that was both physically and spiritually separate from everyday life.

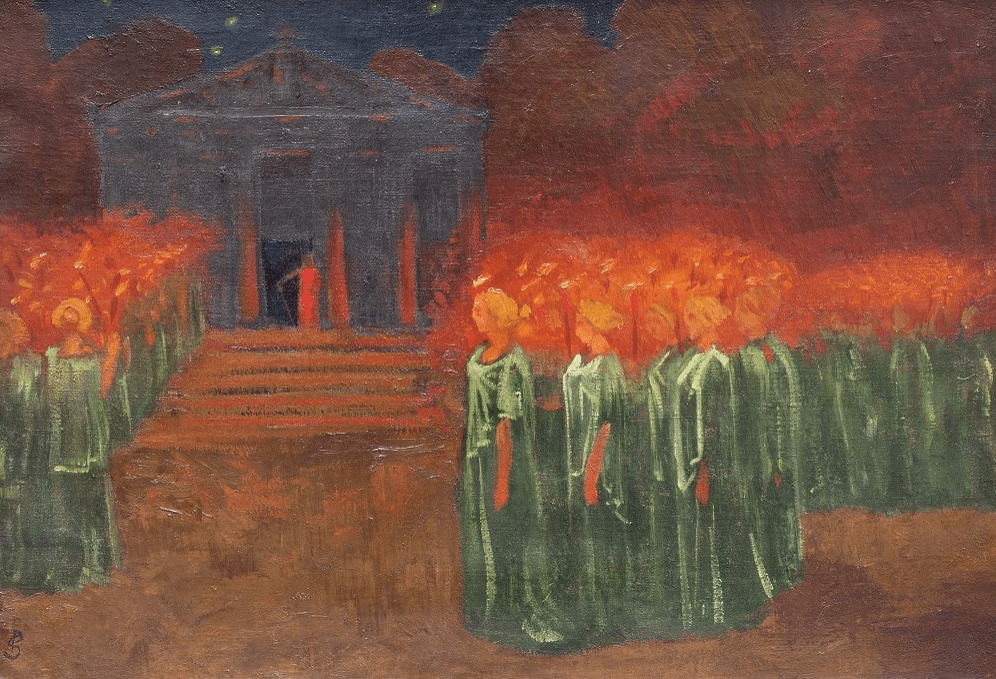

The need for these sacred spaces arose from the Egyptians’ deep connections to their deities and the afterlife. Temples were viewed as earthly residences of the gods, serving as gateways between the human and divine realms—where heaven and earth intersected. This perception made temples the perfect settings for initiation rites aimed at elevating individuals from mundane existence to a heightened spiritual awareness. These rites typically featured ceremonies symbolizing death and rebirth, reflecting the journey of the soul through the afterlife, a core concept in their theology.

The initiation rites were crucial not only for preparing initiates for their roles in society, but also for their spiritual journeys after death. This dual focus on the temporal and the eternal highlighted the critical role of sacred spaces in these rites. Temples provided a controlled environment where metaphysical energies and divine presence were palpable, aiding the transformative experience of the initiate.

The practice of utilizing sacred spaces for initiation rites dates to the very beginning of Egyptian civilization, around 3100 BCE with the First Dynasty. Over the millennia, these practices evolved, but always maintained the importance of sacred spaces in achieving spiritual transformation.

Drawing a parallel to this, Masonic lodges today are considered sacred retreats where initiations and rituals of gradual revelation are conducted. These lodges are deliberately arranged with symbols and tools that reflect Masonic teachings, creating an atmosphere that supports the initiate’s symbolic death and rebirth. The practice of conducting rites in secret or in consecrated spaces is not just a nod to tradition, but is a recognition of the need for environments that are removed from the concerns and employments of the world, enhancing the depth and impact of the transformative processes.

Freemasonry, like the ancient Egyptian practices, operates in these consecrated spaces to maintain a level of confidentiality and sanctity. This secrecy is not just for tradition, but serves to deepen the bond among members and enhance the personal and communal experience of the spiritual and moral lessons imparted during the rites. The use of such spaces reflects a universal understanding of the importance of special environments in facilitating profound personal and community transformations, echoing through centuries of human spiritual practice.